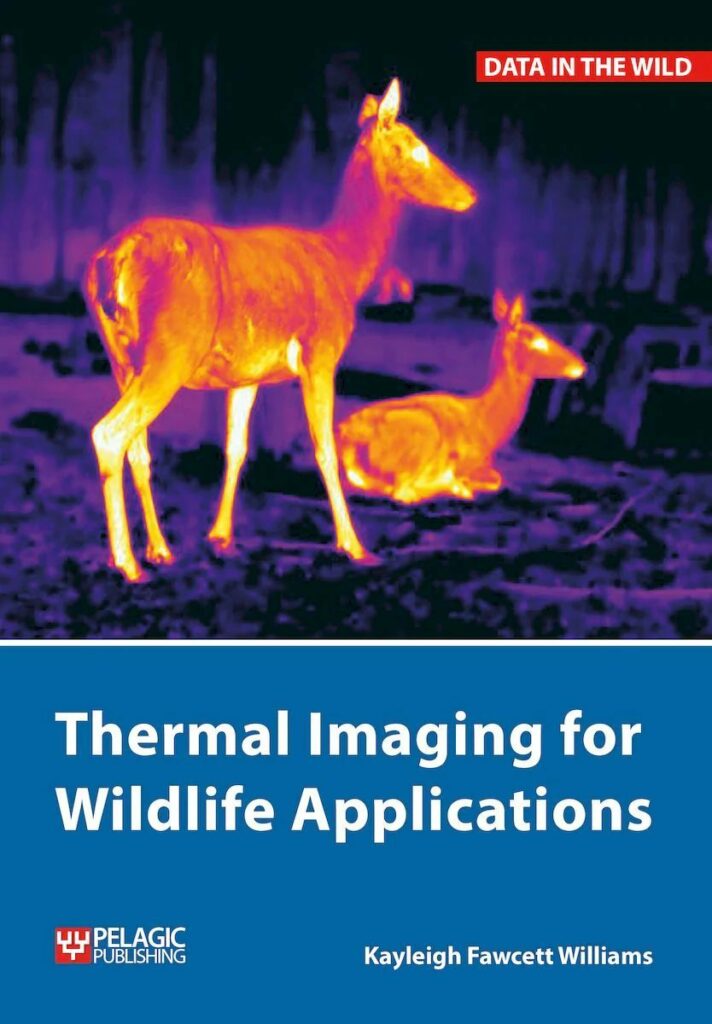

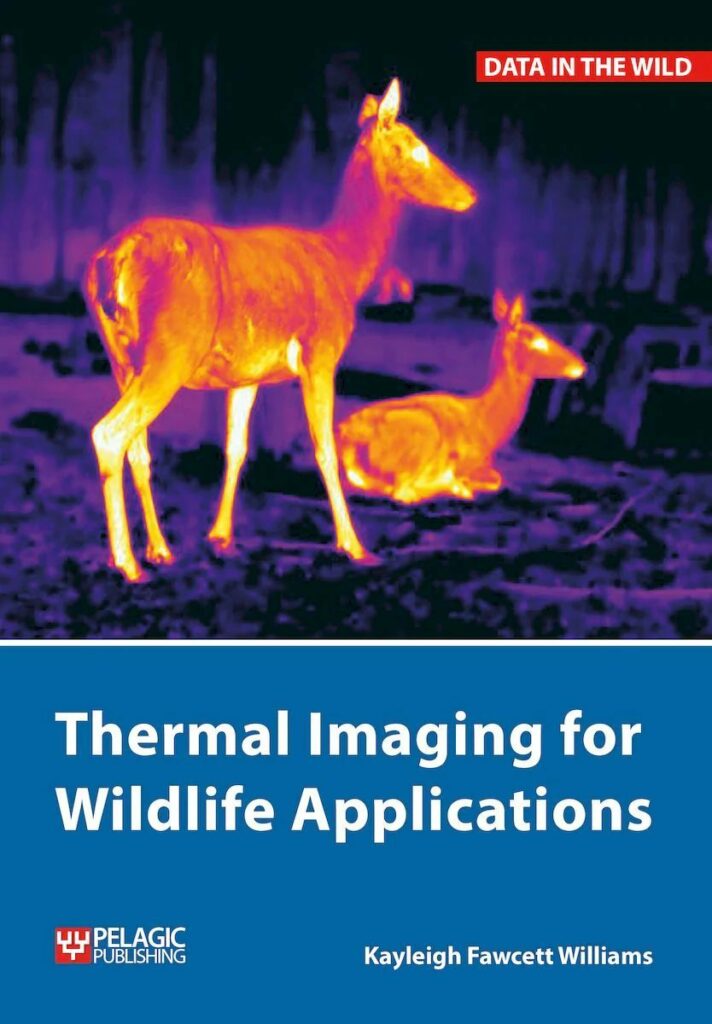

Thermal Imaging for Wildlife Applications offers readers an invaluable and practical guide to this exciting technology. Covering a wealth of basics, including the history of thermal imaging and its advantages and challenges, the book also provides readers with all the information they need to begin choosing and using the right equipment. A chapter on wildlife applications covers all of the main animal groups for which the technology is of use, and a final chapter discusses the future possibilities of thermal imaging.

Thermal Imaging for Wildlife Applications offers readers an invaluable and practical guide to this exciting technology. Covering a wealth of basics, including the history of thermal imaging and its advantages and challenges, the book also provides readers with all the information they need to begin choosing and using the right equipment. A chapter on wildlife applications covers all of the main animal groups for which the technology is of use, and a final chapter discusses the future possibilities of thermal imaging.

Kayleigh Fawcett Williams is a Wildlife Technology Trainer and Consultant and has been using technology for wildlife applications for the past sixteen years. As the founder of Wildlifetek and KFW Scientific & Creative she helps wildlife students, professionals and enthusiasts use technology to improve their wildlife work via her online training and support services. Kayleigh is also the author of the Thermal Imaging Bat Survey Guidelines which were published in 2019 in association with the Bat Conservation Trust (BCT).

Kayleigh Fawcett Williams is a Wildlife Technology Trainer and Consultant and has been using technology for wildlife applications for the past sixteen years. As the founder of Wildlifetek and KFW Scientific & Creative she helps wildlife students, professionals and enthusiasts use technology to improve their wildlife work via her online training and support services. Kayleigh is also the author of the Thermal Imaging Bat Survey Guidelines which were published in 2019 in association with the Bat Conservation Trust (BCT).

During your PhD, you spent some time training to be a thermographer. What did this training involve, and how valuable do you consider this type of ‘formal’ training to be for anyone wanting to use thermal imaging equipment for their work or studies?

My thermography journey really began when I took my Level 1 Thermography Certification. This was an in-depth technical training with the Infrared Training Centre (ITC) at FLIR’s UK Headquarters in West Malling. It was a fantastic grounding in thermal science and kick-started my use of this technology. I always recommend this training to students and researchers who need to know how to carry out temperature measurement. This is usually only for very specialist research applications where the body temperature of the animal that they are working with is needed.

However, it’s definitely not for everyone. In fact, very few wildlife applications require temperature measurement, but all of them require an understanding of how the technology works, its limitations and, of course, its benefits. That’s why I have since developed wildlife-specific training for those that want to use this technology effectively but don’t need temperature measurements.

Thermal imaging equipment has been around in one form or another since the 1960s/70s. Why do you think it has taken so long for it to become more widely adopted?

It’s a long story, which I cover in much more detail in the book, but I think there are two key elements that have affected our adoption of this technology for wildlife.

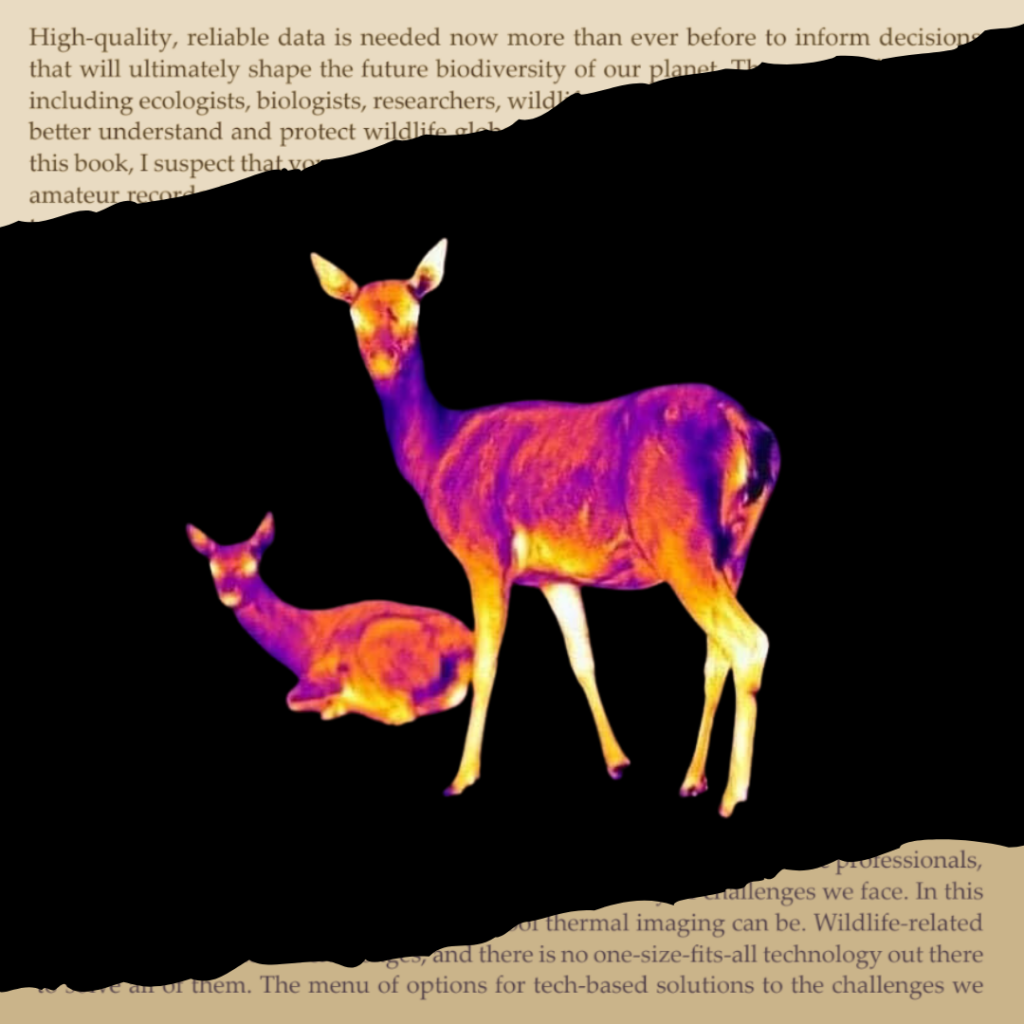

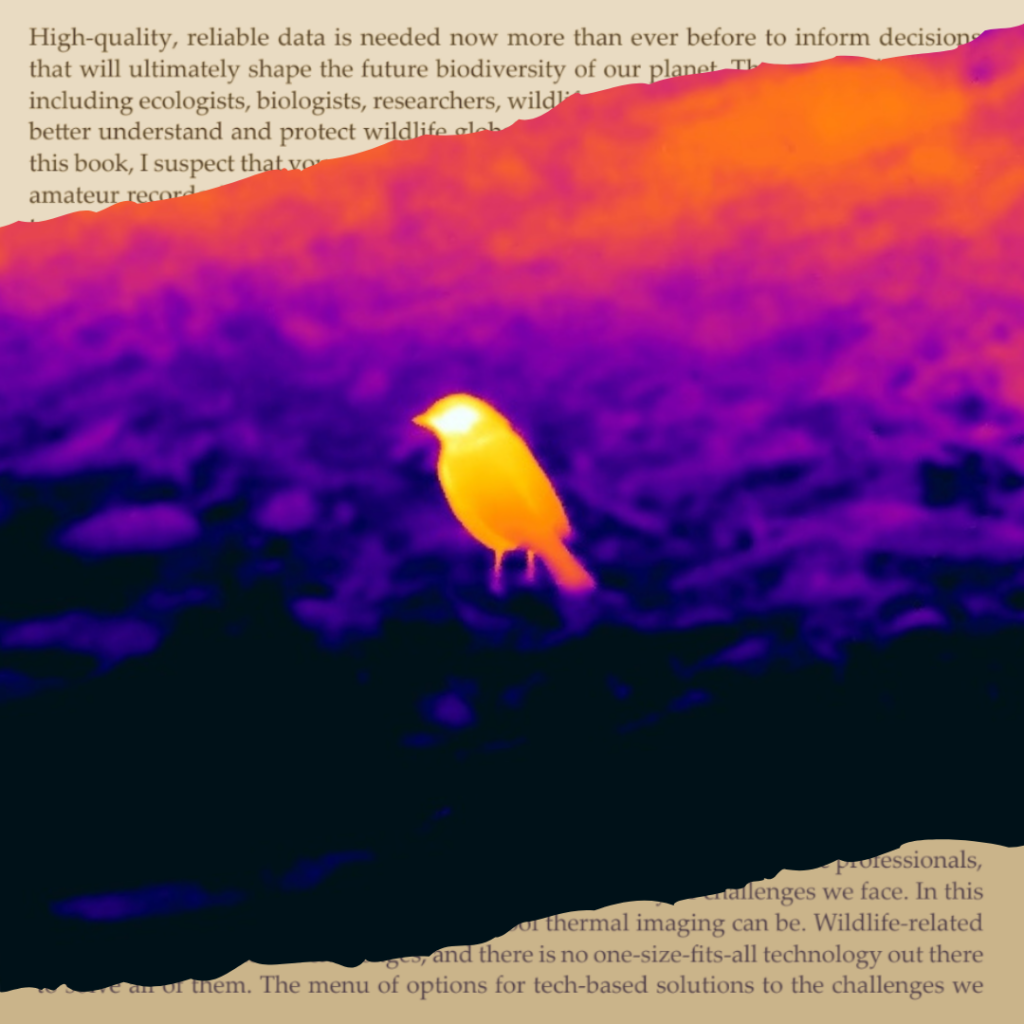

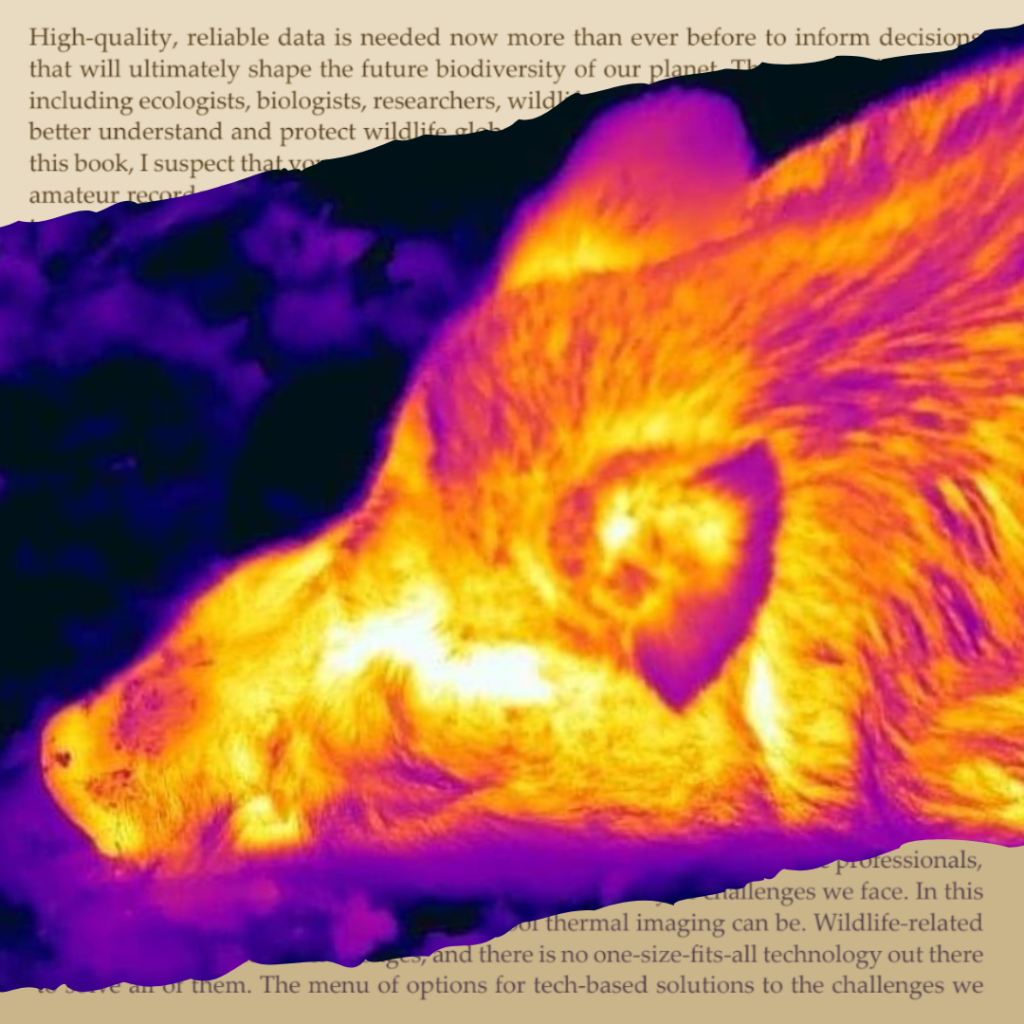

Firstly, a key factor is the nature of the equipment itself. Early thermal imaging devices were expensive and cumbersome, making them largely inaccessible and impractical for most wildlife professionals. Over the decades, we have seen huge improvements in both the affordability and practicality of models available on the market. This has accelerated in recent years, where we’ve seen a massive shift towards the use of thermal imaging by both professional wildlife ecologists and amateur recorders alike.

Secondly, another major influence is the expertise of those using the equipment. Without an appropriate understanding of the technology, many have failed in their attempts to use it effectively. Unfortunately, in some cases this has led to misuse and the spread of misinformation about the technology. This has undoubtedly slowed our adoption of this technology for wildlife purposes.

Among the 300+ documents I reviewed as part of the research for the book, I noticed time and time again that these factors, equipment and expertise, determine the success or failure of thermal imaging for a wide range of wildlife species.

What do you consider to be the main challenges in working with this type of equipment?

Again, it is usually those same two factors we just discussed: equipment and expertise.

The number one question I am asked by ecologists, researchers and amateur recorders is: “What thermal imaging equipment should I buy?”. With an ever increasing list of thermal imaging devices available for us to buy, we can experience a paradox of choice where we can become confused by the array of different options on offer. So choosing the appropriate equipment for a specific wildlife application can be challenging, yet it is absolutely vital to get this bit right.

Once we have chosen our kit, the next challenge is being able to use it effectively. This requires an appropriate level of knowledge and experience, but acquiring this kind of expertise can be difficult, as I found out when I first began my work in this area thirteen years ago. Back then there were very few training opportunities and hardly anyone was using the technique outside of academia. Thankfully, things have changed a lot since then and wildlife-specific training is now available, making it much less of a challenge to access the knowledge and develop the skills that are needed.

The recently published 4th edition of Bat Surveys for Professional Ecologists includes, for the first time, new content on night-vision aids. How much of an impact do you think these recommendations will have on routine bat surveys and their results?

I think the widespread use of night-vision aids for bat surveys will be transformative for the ecology sector. Personally, I have been using thermal imaging technology for this kind of survey for many years so I am well aware of what we can achieve using night-vision aids compared to traditional methods. As a trainer, I am lucky that I also get to see lots of my students experience this for themselves. Many ecologists have told me what a game-changer it has been for them and what a difference it can make to their survey results.

So what have they been missing? Well, in the past, without using night-vision aids, surveyors often battled with the painful but common uncertainty that can lead to writing the words “possible bat emergence” on a survey form. The knock-on effects of these three words can spiral out of control, leading to a raft of unnecessary effort and costs associated with a bat that may or may not have emerged from a tree, building or other man-made structure. On the other hand, we can also easily miss bats using traditional methods. This can of course be costly financially but, more importantly, can lead to harm to the bats themselves.

So it is undoubtedly going to have some massive benefits, but it is also important to consider that, to achieve them, many ecologists out there are now having to get to grips with some new technologies. Some have found this easy and have embraced this change with enthusiasm, while others have a steep learning curve to contend with. Either way, I think it is going to be worth it.

When considering the use of thermal imaging equipment, a lot of attention is given to choosing the right product and designing a suitable survey protocol. However, do you think that the post-processing stage is equally important? And are there widely available software packages that can help with data processing and analysis?

Post-processing and analysis can be just as important, depending on the target species. When used for bat surveys, for example, post-processing and analysis using specialist software packages can make a big difference to the level of accuracy we can achieve using thermal imaging technology. To get those levels of accuracy, however, requires another level of cost in terms of effort, time and investment in software packages. Some software packages for these tasks can be quite expensive, but there are open source options as well. Thankfully, advances in automation procedures are also paving the way to streamlining this process in the future.

Finally, what’s keeping you busy this winter? Do you have plans to write further books?

I do have plans for another book, but right now I am taking a break from writing to focus on something a little bit different. I am currently filming some exciting footage for an upcoming video series called “Wildlife Detectives” on my new YouTube Channel. As part of this I will be using some really cool technologies, including thermal imaging, to find some fascinating wildlife species out in the field. Keep an eye out for it in the New Year!

Thermal Imaging for Wildlife Applications by Kayleigh Fawcett Williams was published in October 2023 by Pelagic Publishing and is available from nhbs.com.

Thermal Imaging for Wildlife Applications by Kayleigh Fawcett Williams was published in October 2023 by Pelagic Publishing and is available from nhbs.com.