An exploration of botany for beginners, How to be a Bad Botanist is a must-read that opens our eyes to the world around us. Through this charming and inspiring work, Barnes takes us on a fascinating journey on the complex nature of plants, and enthrals us with tales to help us appreciate the diversity and wonder of the natural world.

Simon is an author and journalist who has worked on a number of nature volumes, including the bestselling Bad Birdwatcher trilogy and Rewild Yourself. He is a council member of the World Land Trust, a patron of Save the Rhino and honorary vice-president of the Bumblebee Conservation Trust.

We recently had the opportunity to talk with Simon about how plants caught his attention, the importance of botany and how we can all learn to be Bad Botanists.

How to be a Bad Birdwatcher, published in 2004, rapidly became a birdwatching classic and this year was republished as a 20th anniversary edition. What prompted you to turn your attention to plants for your latest book?

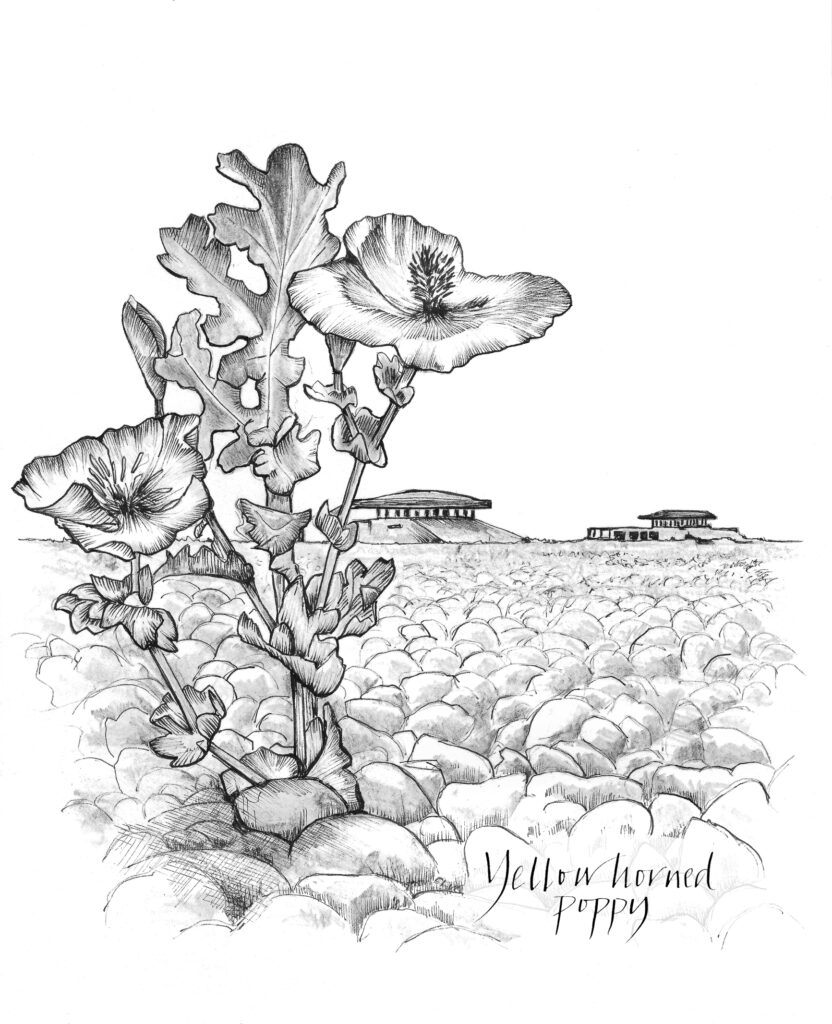

It all began with a damascene experience on Orford Ness. This is a place where military and natural history collide. On the same visit I was able to see a Great White Egret and the casing for an atom bomb. It was, I read, about the same size as the one they dropped on Hiroshima.

My brain was somewhat scrambled by this. After a while I sat on the beach, my mind full of life and death and memories of a visit to Hiroshima, pretending that I was having a bit of a sea watch. It was then that I noticed a colony of plants. Growing in the shingle. Which is impossible. But there they were. Growing. Living. And the extraordinary way that life seeks to live, even in the most difficult circumstances, really rather got to me. These strange plants seemed to make sense of this strange, awful and wonderful place.

I worked out that the plants in question were Sea Pea, Sea Kale and Yellow Horned Poppy: and my own life was better for doing so. Soon, I would be looking at old plants with new eyes.

How to Be a Bad Botanist is a fantastic exploration into the world of plants and botany itself. Where is a good place to start for aspiring botanists?

What’s required is a subtle but drastic mental shift. After my Orford Ness moment, it was clear that plants were now something to do with me. Something personal. I was doing what I wanted aspiring birders to do when I wrote How to be a Bad Birdwatcher. Only with plants.

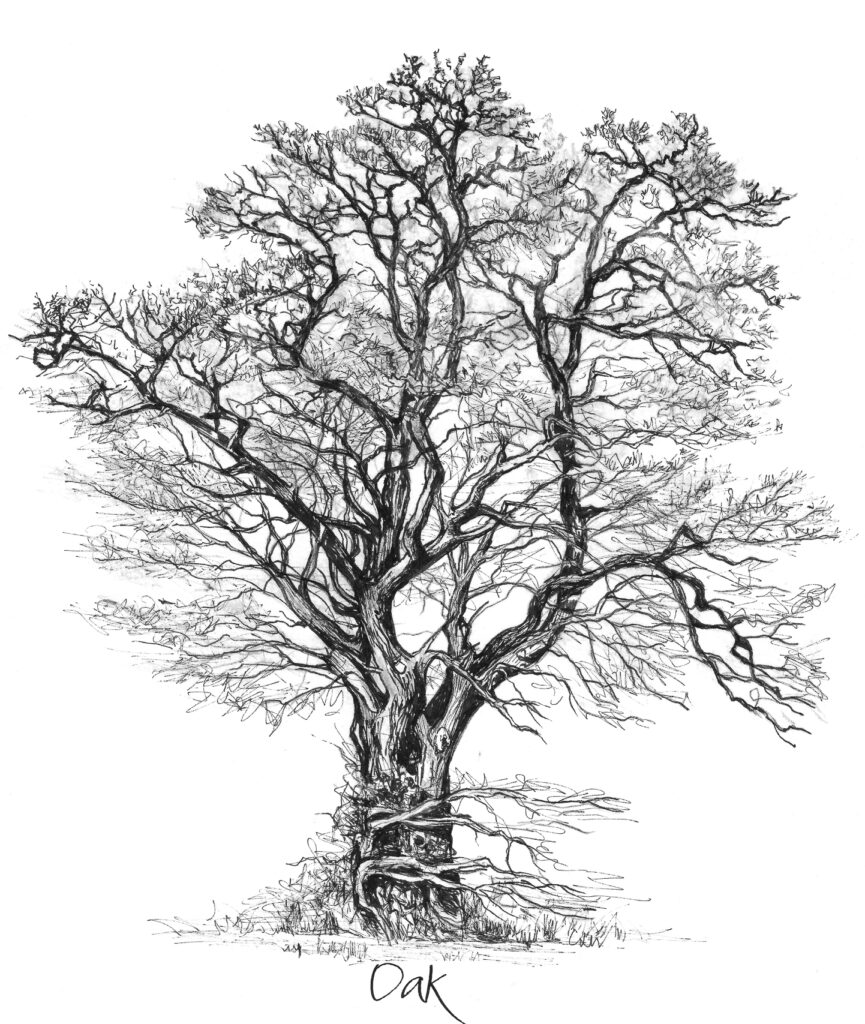

And the first thing I wanted to do was to be introduced. To know the name. Always the first step towards greater intimacy. So, when I saw a tree, I found myself asking, what sort of tree? I made the delightful discovery that I knew more than I thought – oak, conker, holly. It wasn’t the hardest thing in the world to learn a few more – and all at once the adventure was gathering pace.

One of the first things that struck me about the book was how funny it is (I particularly enjoyed “my sitting was devoid of porpoise” when lamenting the lack of marine mammals spotted during a period observing the sea). Do you think humour and levity are important in providing a gateway into a topic that might originally seem highly specialist?

I’m glad you liked the porpoise joke. It’s one of those lines you know you really ought to cut, but haven’t the heart.

And yes, humour is essential. It’s essential to almost everything. Humour doesn’t compromise seriousness. Humours enriches life. There is humour in the greatest art – Ulysses, A la recherche du tempts perdu, Hamlet, The Waste Land, Metamorphoses. Humour humanises, bringing meaning and proportion to all we do. At a funeral, what touches us most deeply are funny stories from the life of a person we have lost.

Humour doesn’t make things trivial. When appropriate, humour makes things profound… in a funny sort of way.

Why do you think that botany is important and what can it bring to our lives?

Everything starts with plants. Plants are the only things that can eat the sun: the power of the sun allows them to make their own food, and that feeds everything else that lives (unless you live in a hydrothermal vent at the bottom of the sea, of course). Lions couldn’t live without plants: they just eat them at one remove.

Those of us who like nature tend to have areas of specialisation, and that’s only natural. But nature itself isn’t about separation: it’s about the way everything fits in together. You can’t really get a handle on your own specialist subject, no matter what it is, without understanding the way it’s driven by plants.

The final chapter relates to a decline of the natural world – what more could we do to support our native wildflower populations in the UK?

The first thing to do is to look after any piece of land you have control over and make it richer and wilder. Sometimes neglect – what conservationists call “minimum intervention” – is the best policy, and it’s assiduously practiced at our place in the Broads.

The second is to support good organisations: your local county wildlife trust (and yes, there’s one for London) and the excellent Plantlife.

And after that, just show people wonderful stuff: here come the waterlilies, this pretty stuff on the riverbank is Purple Loosestrife and Hemp Agrimony, and round the next bend there’s an Aldercarr with nesting herons. By doing so, you enrich people’s lives as well as your own.

Other than buying your book, can you tell us one tip that you give to an aspiring ‘bad’ botanist?

Just look. Look, and seek a name. These days you can use phone apps like Pl@ntNet which will have a decent shot at identifying plants from flowers, leaves, even bark. But mostly it’s about that mental shift: making it personal. Last year it was a nice little yellow flower, this year it’s the first Lesser Celandine of spring and your heart can rejoice.

How to be a Bad Botanist is available to order from our online bookstore.